Introduction: Why Wilmington?

Recently, greater discussion of American capitalism’s roots in slavery has reached the media mainstream through the work of journalists such as those working on the 1619 project, an effort of the New York Times. These authors laudably attempt to destroy the traditional mythos of the early United States as a freedom loving democratic society, and expose it for what it was- a brutal slave state undertaking horrific violence for the sake of accumulation. Ironically though, in most of these authors’ attempts at showing the true basis of American society, they merely pull back the onion one layer further, not all the way to its core- and in so doing create just another ideological origin story. For these writers, and many liberals, once they admit to the United States’ founding on the backs of enslaved people and update their language accordingly, their work is done. Obviously, this is not the case. What is the alternative to this approach to understanding white supremacy and its role in the politics of the US? What is needed is a radical approach, in the sense meant by Angela Davis, of “grasping at the root-” the root not being the ideological system of white supremacy, but the structures of production and accumulation which produced the social system of racial slavery and white supremacy. In other words, what is needed is a historical materialist account, such as DuBois undertook in his classic Black Reconstruction. For those of us living in the southern United States, this means grappling with the successive yet interlocking histories of settler-colonial yeoman society, plantation slavery, sharecropping and tenant farming, proletarianization and industrialization both urban and rural, and subsequent de-industrialization of the ‘sun belt’ and the development of service economies and their surplus populations- processes which are throwing the process of production in many areas of the south back into flux. To understand these historical trends and how they shaped social and political forces is to begin to understand the political economy of the modern-day south in all of its complexities. For those in other parts of the United States and abroad, this history is no less important. Marx remarked in his writings on the American system that American capitalism could not have formed without the institution of plantation slavery, and that the northern industrialist classes were, before the war, just as reliant on the system as the southern planters themselves. Even after the successful struggle against slavery, the primitive accumulation fueled by it remained at the foundation of the industrial north. All aspects of the political economy of the United states were shaped by the institution of slavery, and reshaped by its abolition and the changes in class strcture and society which followed. This makes understanding the class character and dynamics of slavery, reconstruction, and the post-reconstruction south one of the most importants part of understanding American political-economic history.

The Civil War, and perhaps more importantly Reconstruction, determined the manner in which full capitalism was consolidated throughout the former Confederacy, and the nature and interests of the classes which arose to struggle within it. While North American slavery was undeniably capitalist at its core, as an economic mode it lacked some of the features of fully developed capitalism, notably what Marx would call “freedom in the dual sense-” a proletariat living under the conditions of the real subsumption of labor. As the reconsolidation of the southern ruling class took shape in the second period of Reconstruction, it was clear that in the fires of civil war those that survived had been forged from colonial slave masters with delusions of grandeur into a proper land-based rural bourgeoise. The proletarianization of southern labor, however, was uneven- primarily because of the use of white supremacy as a labor management technique.. By the end of Reconstruction, the vast majority of the working people of the south- both black and white- were sharecroppers, since the yeoman settler idolized in an earlier Jeffersonian period had been liquidated by war and the financial panic of 1873. Entry to the waged labor market was carefully controlled: the vast majority of black sharecroppers remained tied to the land of those who had formerly claimed ownership of them well into the twentieth century. Sharecropping served as a rural semi-proletarian holding pattern for a reserve army of labor which would be deployed first in the tobacco and textile boom of the upper south, then to the rapidly industrializing northeast in waves of industrial expansion from 1918-1929 and 1945-1973. This process of proletarianization was a racialized one- white sharecroppers as a whole entered the waged workforce much earlier than black sharecroppers, a division which served as a form of labor management for the developing southern industrialists. Of course, the racist labor protectionism encouraged by the southern bourgeoise and certain craft unions was not truly in the interests of white labor as a whole, many of whom had more interests in common with black sharecroppers and wage laborers than the whites in the halls of power. Despite this common cause, white supremacy proved a powerful ideological tool for the division of the working class in the south, and to this day the labor of all races in the south remains undercompensated compared with more integrated regions of the country- a direct result of white supremacist politics in government, unions, and civic life. As Lyndon Johnson would frankly put it more than half a century later, “if you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket.”

The hateful ideology of white supremacy remains the dominant division within the american working class to this day, and must be grappled with and combated by any socialist movement through the destruction of racist. This process will also have to include the destruction of the myth that white workers gain an absolute benefit from the exploitation of their fellow black workers- a conception that is upheld by liberals, white supremacists, and certain socialists alike. Though by siding with white supremacy white workers may achieve relative gains compared with the status of black workers, this relative gain does not translate to an absolute gain, which we can see by comparing the status of labor in the south with more integrated regions of the United States. This harmful notion does double duty: telling the white worker that the dehumanization and subordination of their fellows is in their interest, while telling the black worker that their enemy lies not in the halls of state power and the boss’s office, but next to them in their workplace. Gaining an understanding of the formation and deployment of this ideology is vital to combating it. Since a full history of the formation of whiteness, white supremacy and its influence on southern class structures is out of the scope of one article, this piece focuses on one event which is emblematic of the transition that American class society undertook during reconstruction, and how various emerging and changing social classes formed a new political-economic order out of the decades-long conflict of the Civil War and Reconstruction. This event is the Wilmington, North Carolina Massacre of 1898, the only successful violent coup d’etat in the history of the United States, and where radical reconstruction breathed its last breath amid the bullet-ridden corpses on the cobblestones.

To understand the forces at play in Wilmington from 1894-1900, the classes and parties which vied for power, and how those groupings changed by the bloody end of the struggle is to go a long way towards an understanding of Reconstruction’s end and the consolidation of the white supremacist class society which emerged. Though by the 1890’s federally-backed Reconstruction policies had been over for years and Democrats had gained control over most of the south, in North Carolina the Republicans had managed to hold onto power through a class coalition known as the Fusion government between black (and poor white) Republicans in the east and white Populist farmers in the Piedmont and mountains. This holdout of Republican rule remained in power long after the ‘redeemer’ Democrats had returned to other Southern states, and posed a viable threat to the emerging post-war ruling class in the state of North Carolina: nationalizing rail infrastructure, extending the right to vote, expanding public education and to an extent promoting the development of a black petty-proprietor class. To the now disempowered eastern landowners and the merchant class of Wilmington, these changes were unacceptable, and they immediately launched a campaign to wrest power away from this developing coalition. They paid for white supremacist speaking tours, bought newspapers in order to run racist stories, and created and supported white supremacist civic organizations. At the same time, they began building a paramilitary force of militias and fraternal organizations. As reactionary forces built up steam, the Fusion coalition made several strategic missteps which began the fracture of the coalition along racial lines. By the time the fires began to burn in Wilmington, it was too late: the paramilitary mobs swept through the city and forced the Republicans out of office by force of arms. This story provides a number of strategic and historical lessons for socialists in the southern United States and throughout the country. By studying this history we can begin to understand better the ways in which the ruling class strikes back against multiracial movements which pose a threat to their continued power. We can also identify mistakes which the Fusonists made which made it easier for the wedge of white supremacy to be driven into the heart of their movement. As is the case for all social systems, learning about the historical process which gave rise to it contributes greatly to a general understanding of class structure in the 20th century south and today. To that end, this article includes an overview of the changes within the mode of production in the south which led to this conflict, then a more fine-grain analysis of production and political-economic geography in North Carolina specifically. Following that is an overview of the principal classes which engaged in the struggle, a narrative of the events in Wilmington from 1894-1900 with some historical analysis, and a discussion of points of strategic importance and implications for struggle in the 21st century .

Equating the antebellum south with a feudal mode of production is a crude categorization often undertaken by ‘stageist’ historical materialists, who understand the Civil War as a kind of liberal revolution against a feudal confederacy. But contrasting feudal estates’ finances with those of slave-capitalist landowners, it is obvious that the plantation classes were immensely concerned with self-reproducing value, or capital accumulation, while feudal estates were engaging in only enough production for self-reproduction of themselves, workers, and their personal prestige. Their mistake is understandable though, when one considers that the class system which existed in the pre-war period was polarized to a similar degree as the feudal system. A tiny planter class had control over the land, the life and death of the people who they forced to labor on it, and maintained private ownership over practically all of the scanty infrastructure in the region, which had been purposefully underdeveloped outside of the estates themselves. The numerically huge class of enslaved laborers which created the wealth of the planters was intentionally kept in extreme destitution, working under brutal conditions. Despite this situation, enslaved workers collectively fought back bitterly against their exploitation, engaging in regular armed revolts, strikes, and slowdowns, though the overwhelming force of the planter class and the challenge of making regional connections outside a single estate made many of these bloody and short. Between the two principal classes were two smaller groups: the overseer class of white supervisors who lived on the estates, and poor whites who came to be known as “mechanics,” an increasingly destitute surplus population who largely made a precarious living hunting, fishing, and trapping. Though the mechanics were not necessarily racial progressives, in this period they were becoming increasingly organized; by the 1850’s some were even threatening to withold support for slavery if their social welfare was not improved. Such a social order was too precarious to last, not only because of the bitter social antagonisms and brutal violence required to sustain it, but because of larger material constraints.

The question of whether the plantation economy was more, less, or similarly profitable than capitalist agriculture remains an open academic question. Regardless of that specific debate, the particular situation of the southern economy by the antebellum period was certainly economically unsustainable. Even before the war, the plantation mode of production faced a material and geographic dead-end. After the 1808 abolition of the trans-atlantic slave trade their labor force’s growth was reduced significantly, requiring the development of an immense and complicated forced migration system in which enslaved workers were shipped around the region to satisfy labor demands, primarily away from the upper south towards the Missippi delta and the cotton operations of the Deep South. After the Compromise of 1850, the geographic growth of the plantation mode was also limited, a fatal blow to a system requiring constant colonial expansion. As a distinctly settler-colonial system relying on forced slave labor, foreign markets willing to purchase surpluses, and the bringing of new land into production to fuel growth, plantationism in one country was doomed to collapse- and the southern elites knew it. The war therefore represented not an ascendant Confederacy asserting their political power in a break from the Union, but an existential fight for the continuation of their economic system- and thus a class war between the southern plantation elites and the northern industrialist class. During the war, fierce class conflict also manifested within the south itself. Enslaved workers hampered the Confederate war effort through work stoppages, slowdowns, and open rebellion. Finally, as the Confederacy’s military might and war fortunes wavered, they simply stopped working or deserted en masse.

After the military victory of the Union, the conflict between southern and northern modes of production had still not been fully resolved. Reconstruction constituted a second phase of the conflict in which the southern economy was re-integrated into the capitalist world market through the dictatorship of first the northern industrialist class, and then the developing southern capitalist class. This dirty war of paramilitaries, coups, and terror campaigns was incredibly chaoltic, and lasted from 1865 until the final violent blows of developing southern capital and white supremacist politicians closed the Reconstruction period in 1898-1900, stabilizing a new class order and mode of production. In the first period, this conflict consisted of the federal occupation of the former confederacy and the transition of its economy through political and military domination. This lasted until the Compromise of 1877, in which the contested 1876 election was brokered through a federal withdrawal from the south. Following this, a new southern capitalist class dominated the transition, one that developed out of the former slave-owning landholder class and enabled by Compromise legislation encouraging the industrialization of the southern economy. This new class began to dominate political rule in the south immediately following federal withdrawal, politically represented by the white-supremacist “Redeemer” Democrats. Though the southern economy continued the trend of slow industrialization in this period, the second half of reconstruction saw the gradual defeat of the struggle by black workers to be included in waged labor or the landholding class. These workers who had so recently fought for and won their freedom from chattel slavery were left friendless with the withdrawal of the federal government and the spread of white supremacist ideology among their potential allies in the poor white classes. Instead, these workers were mostly sidelined into a sharecropping system of labor management, which functioned both as a strategy for surplus labor containment (similar to the function of sharecropping in the Carribean following anticolonial revolutions) as well as allowing rural production to continue at its pre-war pace or faster.

Though the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments to the constitution had smashed the southern mode of production, and some former plantation owners were destroyed by the war and its consequences, reconstruction failed to fully liquidate either the capital (primarily land) or the political power of the antebellum elite as a class. Set back on their heels temporarily by emancipation, the southern landowning class was soon able to transition their labor force to either wage labor or, more commonly, sharecropping and tenant farming. The coastal urban bourgeoise, who made their fortunes processing and shipping cotton, rice, and sugar, largely resumed their prior business, in many cases actually expanding their operations. By the mid-1870s, cotton production was restored to its pre-war rate, fueled by sharecropping labor by both black former slaves and white former yeomen, nearly 50 percent of which were converted to tenancy in the economic turbulence during and immediately following the war and the panic of 1873. Those white yeoman settlers which managed to hold on to their land (mostly in the inland south and Appalachians) formed the narrow middle between the landowners and a vast population of sharecroppers and tenant farmers, joined by a tiny class of small proprietors in the scant cities and towns. The sharecropping class was not given enough land to reproduce their existence in true peasant fashion, nor were they paid in money wages, though formal subsumption had ended with the abolition of slavery. The shares of the product they received functioned as wages in kind, making their relation to rural production semi-proletarian. This class also functioned as a surplus labor population, collapsing into either the urban or rural proletariat through transition to waged agricultural labor or migration to urban industrial areas during the waves of industrial expansion in 1914-1929 and 1945-1979. The southern working classes also included another important although demographically tiny class- the urban proletarian. This class first formed in agricultural processing and shipping in coastal and river towns, and was made up of both black and white wage laborers. As reconstruction and technological progress developed, this class grew in number as more labor-intensive production was undertaken in the south such as tobacco processing and textile production. By the late 20th century, the southern working classes had been almost entirely proletarianized.

The class dictatorship which presided over the transition from the antebellum economy to mature capitalism was therefore tasked with the management of this surplus population and its transfer out of formal subsumption and into the proletariat. In the first stage of this process, the transition was ruled by the northern industrial bourgeoise through their Republican government and the federal military occupation. However, a full transition of the south to an industrial capitalist economy could not be undertaken at this point in history. The possibility of free black people joining the proletariat, as the industrialists may have wanted, was foreclosed by the low level of economic development in the south: the productive capacity of the southern capitalist economy was nowhere near extensive enough to absorb that numerous a class as wage workers. The former southern ruling class also resented being ruled over remotely, and began to develop a political strategy to regain their control over state power. White supremacy, an ideology that was not in any way new to the south but was about to explode into an even more virulent form, was their weapon of choice in splitting the poor whites of the south away from the formerly enslaved black workers. The disputed presidential election of 1876 provided the southern ruling class with the political opportunity they needed when Democrat Samuel Tilden won the popular vote but was challenged in the courts by Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, who claimed that three southern states had illegally distributed their electors. In exchange for a Republican in the presidential seat, Democrats secured the withdrawal of federal forces from the remaining occupied southern states. This transition of rule marked the beginning of the second period of Reconstruction, overseen not by a northern industrialist ruling class but a southern agrarian one. In this period the political measures taken by Republican governments from 1865-1877 were largely walked back, and the struggle for black workers to be included in either waged labor or yeoman farming was violently rebuffed. Though the withdrawal of federal forces marked the end of political reform in the former Confederacy, consolidation of changes in the economic base were not complete. During this second period of transition which lasted from 1877-1900, the southern landowning class re-negotiated control of the labor force and means of production through the sharecropping system and an expansion of industrial agriculture and production, emerging from this process by the mid 20th century as a fully developed capitalist class.

In the state of North Carolina, the pre-war mode of production was particularly unstable. Throughout the state, agricultural production dominated, and by the beginning of the war only two percent of the state’s population lived in cities or towns. Though the products were the same in many cases, the relations in which they were produced differed widely throughout the state’s different regions. Down east, in the plains and sandhills near the Atlantic, a classic plantation economy had developed by the prewar period, a polarized system characterized by large landholders extracting enormous amounts of value through the formal subsumption of enslaved labor. This economy was almost entirely extractive, and relied on the industrialized northern states and Europe for processing and export of their goods through shipping out of the port cities of Wilmington and New Bern. Railroads were few in this period, and those that existed did not penetrate far into the state but primarily collected goods from the eastern region for export by sea. In the central Piedmont, and especially in the western mountain regions, large-scale plantation farming was rare, and most of the economic activity in these areas consisted of yeoman settler homesteads, which produced goods for their own reproduction as well as for market in nearby towns. The small-scale nature of production in the central and western regions was due to both the lack of easy export methods and more difficult terrain and soil. For these reasons, the western two-thirds of the state’s economy was largely self contained until immediately before the war, when the connection of the two segments of what would become the North Carolina Railroad completed a route from the foothills to the port of Wilmington. Though the railroad expansion could have meant the expansion of the large-scale plantation economy into the Piedmont, history intervened: the Civil War broke out just a few years later, throwing the economy into chaos. It was not until after the war that the railroads would be consolidated into one system, leading to easier export and an expansion of large scale tobacco and textile production in the Piedmont and mining, logging, and other extractive industry in the mountains.

Because of the profoundly different modes of production that existed within the state, each region had distinct economic interests when it came to secession and the Civil War. The Piedmont and mountain regions largely opposed the Confederacy, not out of any radical abolitionist commitment but simply because it would mean going to war for an economic system and way of life which was not their own. The eastern region, however, was the most economically powerful as well as the most populous, and their interests lay strongly with the Confederacy. This conflict caused bitter fighting within the state government over the question of secession from the Union, and it was not until the state was geographically surrounded by the Confederate states of Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina that it too seceded on May 20th, 1861. During the war, North Carolina remained divided, providing the most troops to the Confederacy and the second-most troops to the Union out of any southern state. This division remained largely true to the eastern-western divide of production within the state, with most of the Union troops coming out of the mountains, and the mountains providing the Union with a base of support, especially in the later war. The state was significant not only for troop recruitment but as an important battleground. Many of the war’s important battles of the Western theater were fought on North Carolina soil, and the surrender of General Johnston which effectively ended the war took place near Durham, North Carolina at Bennett Place.

But when the military war ended, the class war was far from resolved. In fact, though the terrain of the geographic and class conflict within the state changed dramatically, neither side’s position was destroyed by the conflict’s resolution. After the failure of federal reconstruction policy to smash the plantation owners as a class, they reconsolidated into a new landowning rural bourgeoise, extracting their surplus through wage and sharecropping labor rather than forced enslavement. The class which dominated the Piedmont and mountain regions, the yeoman settlers, gained a natural electoral ally against the political power of the eastern landowners in the newly enfranchised black workers. The coalition between these two classes in an attempt to break the power of the eastern landholders and seize control of the state government would be known politically as the Fusion strategy, as it involved the fusion of two parties, the Republicans (who had the support of the recently-enfranchised black voters as well as poor whites) and the Populists (whose base consisted of farmers and small proprietors from the Piedmont and Appalachians). This conflict would rage across the state from the withdrawal of federal troops in the compromise of 1877 until the decisive final blow in Wilmington, 1898.

The Republican party after the war consolidated a base of support among newly enfranchised black workers as well as attracting poorer whites, especially veterans of the Union army. Black voters overwhelmingly went Republican to defend the gains of emancipation and further expand their freedom, and both groups were attracted by redistributive policies, progressive agricultural loans, and promises of infrastructure and educational funding. The Populists were also a relatively new party, having been incorporated into a party in 1892 out of a coalition between the Farmers’ Alliance and labor groups in the midwest. The Farmers’ Alliance had been established in the mid-1870s in order to combat crop-lien loaning and other predatory loan practices which had emerged out of the crisis of the agrarian economy caused by emancipation and the mid-1870s economic depression. The organization also fought for the establishment of an income tax and reform of the railroad system, which imposed heavy fees on farmers trying to export their goods. This group was composed of three branches, the Northern alliance (whose base was primarily in upstate New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio) The Southern Alliance (which was comprised of white smallholders throughout the former confederacy) and the Colored Alliance (made up of farmers excluded from the Southern Alliance by their regressive racial policy). This racist tendency for political segregation would remain a hindrance to the Farmers’ Alliance as well as the later Populist party, especially when attempting to form coalitions with more racially diverse union movements such as the Knights of Labor in the north and midwest. Following the incorporation of the Populist Party in 1892, they adopted a platform which included agricultural loan reform, nationalization of railroads, and a redistributive income tax. Though the party enjoyed extensive support among farmers, it never achieved national prominence, probably because of its single-issue focus on agricultural policy. Through the elections of 1894 and 1896, the Populists struggled to win over labor bases in the Midwest and North, a population that they counted on for their national coalition. By 1896, the national party had largely collapsed and merged with either the Democrats or Republicans. In North Carolina though, a large population base of yeoman farmers and a strategic coalition with the Republican party provided the Populists with enough of a base to remain in the government coalition all the way through the reactionary wave of 1898-1900.

In early 1894, the Republican and Populist parties agreed to a tactical alliance within the state of North Carolina. Though no formal structure for organizational fusion of the two parties existed, opponents began referring to the coalition as the “fusion party,” and the name stuck. The strategy proved wildly successful, and in the election of 1894 the Fusion coalition swept the General Assembly, Supreme Court, and every congressional seat which the coalition contested. The government which convened in 1895 took action on several of their campaign issues, including further expansion of the voter franchise, increased funding for public education, and debt relief for farmers. But despite nearly unanimous support from the voting parts of the state’s black population the Fusion government included only one black representative due to nomination practices within the party. Though those in government claimed that they were planning to work to increase black representation in subsequent elections, more radical critics believed that the party’s invitation for black support in government was a cynical strategic move, not a principled stand. This criticism was mostly leveled against the Republican candidate for the 1896 gubernatorial campaign, Daniel Russell. Russell had previously been a Democrat and had, earlier in his career, run promising to prevent “negro rule.” This briefly split the North Carolina Republican party into two factions, dubbed “pro-Russell” and “anti-Russell.” Though both factions eventually re-formed the bloc with the Populists for the 1896 election, this split over the opportunism of some white Republicans would remain below the surface. In the elections of 1896, the reunited Fusion movement expanded its already considerable governing power by an order of magnitude. Russell claimed the governorship, and several Republicans and one Populist were sent to the national legislature. This gave the Fusion government control of all three branches of state government, as well as the state’s voice in the national capitol. The 1896 government undertook a further expansion of state funding for schools and other municipal-level welfare, as well as implementing state ownership of the North Carolina Railroad, though operation remained on a privately operated lease basis. With a strong demographic majority, a virtual legislative mandate, and after following up most of their campaign promises by implementing policy, in 1897 the Fusion government seemed primed to be the ruling party in the state of North Carolina for the foreseeable future. In fact, it would rule for only another year, and its power would be completely and irreversibly broken by the turn of the century.

Wilmington in the final decades of the 19th century was the largest city in North Carolina, one of the most economically and militarily important ports on the southern Atlantic coast, and the center of a developing post-war southern economy. It was also a majority black city, but had been ruled by a narrow white political establishment for its entire history. Most black Wilmington residents worked at the docks- the main economic engine of the city- though some worked as domestic servants, artisans, and shopkeepers. The almost entirely black neighborhood of Richmond had a newspaper, fire department, dance halls, and several churches which served as the neighborhood’s centers of civic life. Needless to say, black Wilmington voted overwhelmingly for the Republicans in the municipal elections of 1897, and the city as a whole swung decisively towards Fusion. However, the racial cracks in the Fusion coalition which had first appeared earlier that year in reaction to the Russell campaign began to grow. Fearing a reactionary backlash should the will of the people of Wilmington be actually represented in the municipal government by a black majority on the Board of Aldermen, the state-level Fusion leaders chose not to redraw the gerrymandered districts of the Wilmington legislative map. Even though this damaged their further electoral prospects, they viewed the potential for conservative backlash as more dangerous than diminished electoral returns. The state government then also converted the Board of Aldermen from a directly-elected body to a partially elected, partially appointed body as a final bulwark against a black majority in municipal government. Despite these betrayals by the state leadership, the Fusion parties carried the Board 5-3-1 (one candidate from the Silver Party was elected). But despite this victory for Fusion, due to gerrymandering and the appointment system, only one black Alderman was elected to the board. And of course, despite their intentions, this conservative soft pedaling did more to damage their own coalition than to placate the Wilmington bourgeoise and Democratic leaders, who were already scheming their first planned coup by the time election results were published. Egged on by a small committee of Wilmington capitalists and state party leaders, the three Democratic members of the Board of Aldermen declared the election results unconstitutional, and formed a rump Board, to which they soon added the six defeated Democratic runners-up. This led to a few days where two bodies claimed to lead the city of Wilmington, both the democratically elected board and the unanimously Democratic holdouts. Despite the audacity of this move, it was upheld in the county court, and it took an appeal to the state Supreme Court, which had been secured by the Fusion coalition in 1894, to bring the three rebellious Democrats to heel. Their attempt at a soft coup now defeated, the ruling class of Wilmington and their friends in the Democratic party began to look towards the elections of 1898 as their time to regain power.

After the failure of the Board of Aldermen coup, members of the Wilmington Merchants’ Association and the Chamber of Commerce began to meet secretly in order to decide how their power could be restored. After talking with leaders from the Democratic Party, they decided to attack the Fusion government where it was weakest: at the racial divide. This strategy would be known to this group as the “White Supremacy Campaign,” but bears resemblance to the 20th century concept of the strategy of tension. The reactionary journalist H.L. Mencken later summed this up by saying “the whole point … is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins.” This strategy, they hoped, would destabilize the Fusion government through a two-pronged approach: first an ideological campaign to show the weaknesses (both real and conjured up) of the governing coalition, followed by scare tactics designed to drive the population towards the "stronger" and more protective option.

The first part of the white supremacy campaign of 1897-1898 unfolded across the state soon after the elections of 1897. The Democratic party funded riders to every town across the state to give speeches attacking the Fusionists. Their rhetoric consisted of both typical conservative arguments against public spending, such as concern about debt and taxation, but also an attempt to argue that the Fusionists were simply puppets for "negro rule." This took the form of a common bogeyman of the campaign, "Republican-negro rule." This tactic bled poor white support from the Fusion government where it was able to convince them they were being duped into electing a government that eventually would not represent them. Ironically, of course, the white Republicans in leadership were a long way from giving up their white-knuckle grip on power, as evidenced by the undemocratic Board of Aldermen appointments of the previous year. The Democratic party and Wilmington-based capitalists also funded several civic and paramilitary groups which would serve as their shock troops of repression and terror. Some were civilian in nature, such as the White Government Union, which spread racist literature and speeches throughout the state, and the White Laborer’s Union, which attempted to split white workers away from their fellow black workers at the docks and shipyards. The strategy of breaking working-class coalitions through providing marginally better compensation and work to white workers in exchange for their loyalty would be a strategy that did not end with the events in Wilmington but remains in effect to this day. The party and business organizations also funded more dangerous groups such as the Redshirts, a white supremacist paramilitary organization which had first surfaced several years earlier in South Carolina. This group mainly served as a tool of political repression wielded against black residents, though in the days leading up to the election they became increasingly bold, eventually leading an unsuccessful attempt on Governor Russell’s life as he traveled by train through their active territory. Finally, there was the Wilmington Light Infantry, an institution which was largely made up of the sons of Wilmington society fixtures and well-known businessmen. Some of the officers who oversaw this body had seen military action in the Spanish-American War earlier that year, and had come home with military training. Though the WLI was technically a militia, not a state force or a party paramilitary unit, its social position as a club for the sons of Wilmington high society resulted in its de facto control by the Wilmington ruling class and by extension, Democratic party officials. In this period the Democratic party also consolidated control over one of the state's most important newspapers, the Raleigh-based News and Observer, and began to run sensationalist and false articles about criminal activity and rapes allegedly committed by an emboldened black population, in the hopes that rural white voters would be threatened into the arms of the racist Democrats.

It was, incidentally, a newspaper article which provided the Wilmington bourgeoise with the excuse they needed to eventually spur their paramilitary mobs to action. On August 18th, 1898, Alexander Manly- editor of Wilmington’s black newspaper the Daily Record- wrote an editorial attacking a recent speech by white supremacist activist Rebecca L. Felton, in which she had argued that lynching was a necessary part of protecting rural white women from rape. Manly’s objection to this piece of white supremacist rhetoric soon drew derision from Democrats not only in Wilmington, but from around the south. Senator Ben Tillman of South Carolina threatened that Manly would have been “food for catfish” if such an article had been published in his district. In Wilmington, Democratic leaders and merchants began to agitate against Manly and his newspaper. Bands of paramilitary organizations began to patrol the streets of Wilmington, and skirmishes began to break out along the borders of Richmond, where black residents had begun to arm themselves in self-defense. In this tense atmosphere, community leaders in the neighborhood began to prepare for the worst. George H. White, a black representative from North Carolina, appealed to President McKinley for federal military aid, fearing an armed revolt was about to break out. But McKinley refused, arguing that sending troops into a southern state so soon after the Compromise of 1877 could reignite open warfare. He finally agreed that if every local option was exhausted and the threat remained, federal forces could be utilized. But in Wilmington, elites largely controlled the militias which were the local forces in question, and simply refused to use them. This essentially stymied local attempts at marshalling the forces of the state for the defense of Wilmington’s black population. Without federal support, the communities began to arm themselves as best they could. Because all major arms companies were embargoing civilians in Wilmington in fear of violence, the neighborhood defense efforts were limited to scrounging together what weapons they already had for hunting and defense- mostly pistols, shotguns, and outdated hunting rifles. The Redshirts, WLI, and white citizens’ militias, on the other hand, were supplied with military-grade Winchester and Sharps rifles as well as two wagon-mounted rapid-fire guns. Following a skirmish in which a white civilian was wounded by a shotgun blast, all black-owned guns were confiscated on sight by patrolling paramilitaries- worsening their strategic situation considerably. The night before the election, Democratic leader Alfred Moore Waddell led a “mass meeting of white citizens” in which he proclaimed “we shall win tomorrow if we have to do it with guns!” and called for the killing or exile of any black voters seen at the polls.

Despite the violent rhetoric being spouted by the White Citizens' Meeting, no violence initially erupted as the Democratic machine rolled over the voters of Wilmington. WLI troops and non-uniformed militiamen stood at every corner with their Winchesters, ready to quash any rebellion to the ballot-stuffing taking place, and black community leaders called for the neighborhood to hunker down, fearing a violent result. The Democrats’ fraud was unabashed: in the city’s strongest Republican precinct where only 30 Democrats were registered to vote, nearly 200 Democratic ballots were counted after a mob took over the precinct, extinguished all the lights, and threw out the black precinct officials. Poll officials across the city were threatened and told to “look no white voter in the eye” in order to determine whether the person voting was who he claimed, and several cases of voting under the names of the dead or absent were later proven. At the end of the day, the official count declared a Democratic victory- the fusion government had been broken. As the sun set, no blood had been spilled and not a shot had been fired. But though the Fusionists power at the state level had been broken, the Fusionist municipal government of Wilmington still stood, and elites of Wilmington and their street mobs were not yet sated with blood.

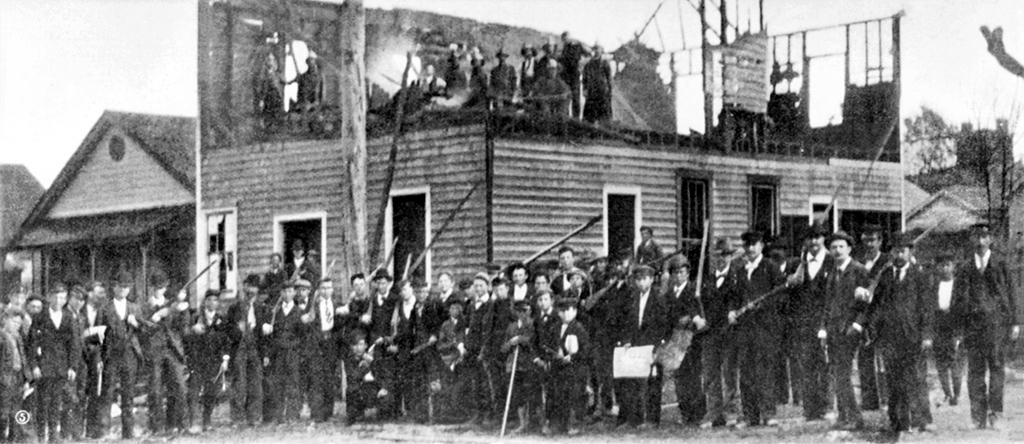

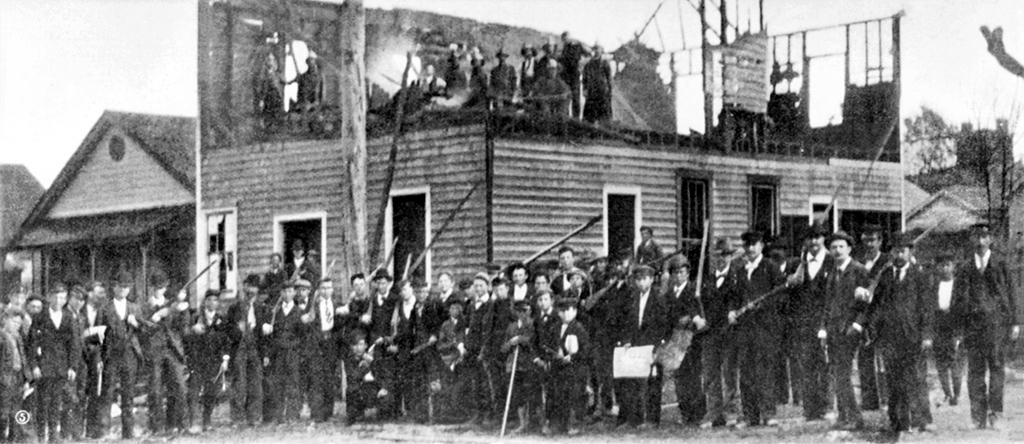

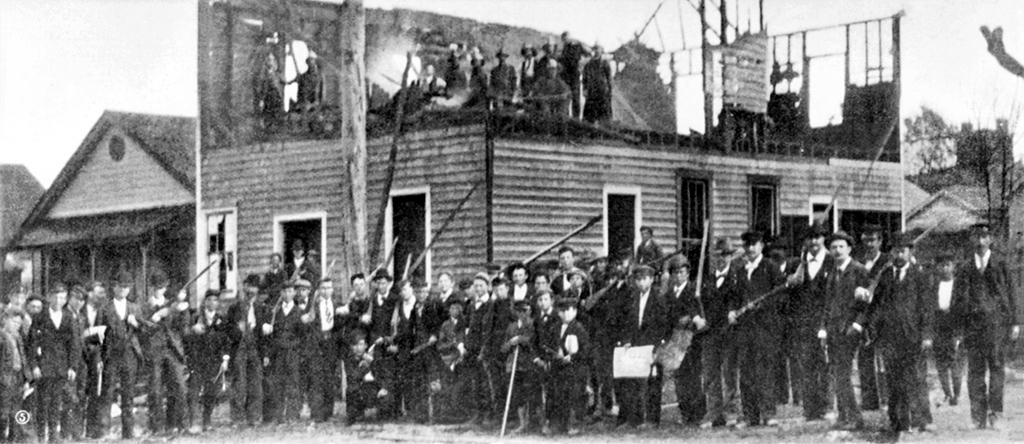

The next morning, some of the prominent Democratic leaders who had formed the initial secret planning group with the merchants and capitalists of Wilmington called for another mass meeting. In this meeting, they touted their fraudulent victory and unveiled a document which would come to be known as the “White Declaration of Independence:” a document which made clear their vision for the government of North Carolina. Within this declaration the Democratic leaders rejected outright any government containing black representatives, calling the current governing coalition unacceptable. Their rationale for this statement was simple: since the majority of the state’s property owners were white, they should be the ones who decided where the state’s resources went. The Declaration also demanded the closure of the Daily Record, the paper which had dared respond to a pro-lynching argument earlier in the year. This declaration was sent to a meeting of black leaders, who had convened in a response to the crisis. They drafted a response which was mostly acquiescent, agreeing to close the Record and respect the results of the fraudulent elections, although reminded the Democrats that as they still did not hold the municipal government they could not rule on any matters within the purview of the City of Wilmington. This response was sent by courier to Waddell, the other Democratic leaders, and their mobs. Though a telegram had been sent to Waddell notifying him that a response was on the way, he decided to seize on the courier’s delayed arrival to make his move for ultimate power. Lying to the mob assembled outside, he proclaimed that the black leaders had not responded, and that it was time for them to take matters into their own hands. Waddell personally led the mob, marching in military formation, to the door of the Daily Record, where an unidentified member of the crowd struck a match and the building began to burn. The neighborhood’s all-black firefighting team soon appeared, but were met with armed resistance when they attempted to put out the fire and had to content themselves with merely containing the blaze to one building. Before long, the Record had burned to the ground.

Nearby, the first gunfire of the day erupted in the nearby mixed-race neighborhood surrounding Fourth and Harnett streets, on the border between the white and black sections of the city. Two opposing groups had formed across this corner, the white group threatening to enter the neighborhood and the black group keeping watch. Though reports differ on who fired the first shot, the situation quickly developed into a running firefight through the street. During the first exchange, the much better-armed whites killed or wounded several people, while taking no casualties. But during the subsequent chase and firefight, as they tried to penetrate deeper into the black neighborhood, they came under fire from buildings along the street, and a few paramilitaries were severely wounded. This incident became a rallying point for the mob, and the shooting was quickly pinned on Daniel Wright, a black man who owned one of the houses on the street and was known to be armed. The mob descended on his house and Wright was clubbed over the head and dragged into the street, his house burning to the ground behind him. One man in the crowd then told Wright to “run for his freedom.” According to a witness, before he had made it 50 yards down the street, the crowd had fired more than 40 rounds, hitting him 13 times in the back. The killing of Wright was not enough to avenge the mobs for the wounding of the paramilitaries in the early skirmish, and following this incident the heavily armed WLI made a coordinated advance into the neighborhood of Brooklyn, bringing with them their wagon-mounted machine gun and orders to shoot to kill. This column was fired upon as it advanced through the corner of Sixth and Brunswick streets, and though the shot missed, the machine gun team began to fire indiscriminately into the crowd, killing at least 25 and discharging hundreds of rounds into nearby houses. When one of the WLI cadets attempted to refuse the order to fire, the Spanish-American War veteran in charge of the team threatened to shoot anyone who refused orders. Following the mass killings at Sixth and Brunswick, the WLI and paramilitaries moved relatively unopposed through the neighborhood, strategically taking control of organizational centers such as churches and major businesses.

Throughout the remainder of the day, disorganized violence continued as paramilitaries and white citizens continued to kill anyone who was deemed a rabble-rouser or troublemaker. Several more key buildings were destroyed, including businesses and the neighborhood’s dance hall, a major cultural center for the city. The violence was only ended by the setting of the sun, which descended over a burning and blood-soaked city. At least 60 and as many as 200 people had been killed, and many more beaten or wounded. But perhaps the most historically significant change did not happen during that bloody day, but the long night afterwards. Hundreds of black families had begun to prepare to leave the city as soon as the mob marched on the Daily Record that morning, and under cover of night, a steady stream of people flowed away from Wilmington, through the marshes and grasslands to nearby towns. Many never returned, permanently hollowing out the neighborhood of Brooklyn and breaking the power of social organizations there. Overnight, Wilmington had gone from one of the few majority-black cities in the country to a majority-white one.

As shots still rang out in the streets, Democrats moved to take control of the last seat of power which was still under fusion control- the municipal government of Wilmington. During the secret series of meetings between the merchants and capitalists of Wilmington and the Democratic Aldermen, selections had been made as to who would be appointed should the opportunity arise, and those appointees were quickly brought forward. The WLI was dispatched to round up the democratically elected Aldermen and march them to city hall, where they were told they must resign, since there was a mob outside and the mob’s leaders could not guarantee their safety if they did not. The single black alderman serving on the board later estimated that there were 200 armed men in the building awaiting their answer. All resigned, and were subsequently replaced by the Democratic appointees. In the following days, the Fusion aldermen as well as prominent Republican leaders were banished from the city by the WLI and Redshirts, some never to return.

The day after the coup, Wadell and his new cabinet of appointed aldermen moved to consolidate their hold on power, appointing 38 ‘temporary policemen’ from the ranks of loyal paramilitaries to maintain order and squash any further resistance. They then embarked on a campaign of regime change so complete the only appointed official left in municipal office was the fire chief, mostly giving away official positions to fellow members of the murderous mob. Explicit effort was made to scrub black residents of any official representation, to such a degree that even the all-black firefighting squad who had saved the rest of the block after the burning of the Record were fired and replaced by whites. When the new state government convened in early 1899, all reforms undertaken by the fusionists were repealed, and the first Jim Crow laws were passed, including segregation measures and a literacy test for voting. In the statewide elections of 1900, the changes brought about by violent coup in 1898 were given an official veneer when offices were swept overwhelmingly by the Democratic party- which would maintain one-party rule over the state for the next seventy years.

What the Fusionists and Democrats had been struggling over in the period of transition was under what terms full capitalism would be brought to the south. Though since the early 19th century the plantation system had been a capital-producing one, as well as integrated into the capitalist world system, there was little wage labor, and much of society at the local level was not governed by the market. Reconstruction meant a transition to full capitalism for the south, and after the federal occupation’s withdrawal in 1877, this would be done on the terms of one southern class or another. The Democrats had their base of power in the old planter class, which was now aligned with the coastal ‘big’ bourgeoise which presided over shipping, trading, banking, and agricultural processing. They envisioned a capitalist society in which social roles changed very little, and they continued to preside over a large mass of value-producing laborers with little to no education or social prospects. They also were invested in maintaining the racial caste system as a labor management force even as they transitioned away from racial slavery. The Fusionists’ power came from a collection of smaller classes that could be collectively called petty-bourgeois. This was a multiracial class, made up of both black and white small proprietors in the east as well as white farmers in the west. Accordingly, their vision for the south in the capitalist mode was very different from the Democrats’. The Fusionist vision for the state of North Carolina was something like an idealized liberal society, in which individual enterprise and education were valued, and various petty producers and proprietors of both races sold their wares on the market. For the developing proletariat of Wilmington and other towns around the state, this was insufficient for their welfare, but ultimately in their interest. Thus, most poor urban workers, black and white, threw in their lot with the fusionists as the working classes of Europe had done with the liberal revolutions of the decades before.

But instead of the European revolutions’ historical structure- ancien regime pitted against capitalists big and small- this conflict took place within a capitalist class society, albeit a very new one. The two political coalitions which battled for power were both capitalist classes, though of a different scale and scope. The rural and urban ‘big’ bourgeoisie with their land, storehouses, and dockyards had come out of a class which was previously not quite capitalist, but now thoroughly was. Upon their victory the social structure which was consolidated was not a regression to a previous mode of production- an option which had been destroyed both through the economic and geographic eclipse of the plantation system and also by the Civil War and early reconstruction. Instead they formed a capitalist class society on their own terms, employing their physical capital to industrialize the Piedmont and mine the mountains, and their political power following the coup to consolidate a regime which would have a stranglehold on the state into the 21st century. The Jim Crow caste system which developed after 1877 in most states and after 1900 in North Carolina, was this regime’s method of managing any potential opposition to their rule. For poor white people, it offered a ‘psychological wage’ as social control- the understanding that whites would be offered economic and social protection from competition in the labor market. For black people, it was brutally coercive social control which took the form of state and mob violence. Though the struggles of the 20th century made critical gains against the state-sanctioned elements of this system, many of its rulers and their descendants remain at the helm of southern capital, despite the destruction of the plantation system and the collapse of the planters as a class. In the fires of the reaction to reconstruction, this class was re-forged as an agricultural bourgeoise, who would ride the sharecropping labor of surplus laborers and the proletarianization of yeomen into the textile and tobacco booms of the late 19th and early 20th century. Even today, as new flows of tech and finance capital pour into post-industrial southern cities from the north and west, the blood-soaked family names of the old south haunt the halls of power and the boards, foundations, and organizations which walk them.